The Russkies are back in Stranger Things 4! In other times, I might have talked about the typecasting of Russians as villainous in American media, but given that Russia continues to commit atrocities in its imperialist war against Ukraine, I don’t really feel like that right now. So let’s talk about Vecna!

Yes, if you hadn’t heard, the main villain in the new season is Vecna! Not the actual Vecna from D&D, of course, but just like the “demogorgon” and “mind flayer” in seasons 1 and 2, the big bad from another dimension gets a catchy moniker from the kids based on a fantasy monster in order to make sense of these alien antagonists.

Wizards of the Coast released a “Vecna Dossier” on D&D Beyond to cover the (slightly retconned) in-game history of the villain, but I wanted to take a look at the publishing history of Vecna himself and his creature type, the lich, including some (probably!) Slavic folklore influence on the monster.

History

The lich came first in the 1975 Greyhawk supplement to the original D&D rules. Here, the lich was just an undead spellcaster without a lot of the flavor that has since been associated with them. The actual word, “lich,” is an archaic English word for a corpse, still seen in terms like “lichgate,” the covered entrance to a churchyard where a body was kept before burial. While there were many undead sorcerers in the pulp fantasy works of Robert E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, and others who influenced D&D, Gygax himself stated that the direct inspiration for this monster came from Gardner Fox, who debuted the creature in his 1969 short story “The Sword of the Sorcerer.”

The name Vecna would pop up a year after the Lich in the 1976 Eldritch Wizardry supplement. Vecna, however, was only mentioned in the backstory in the two artifacts that bear his name: the hand and eye. These were written not by Gygax, but by Brian Blume, one of the controlling partners of TSR, the company Gygax had founded to print the D&D game. The name came about as an anagram of Jack Vance, another writer favored by Blume and Gygax and whose Dying Earth stories inspired D&D’s system of memorizing spells. Vecna was, according to the flavor text here, long dead, and we would not get much more information about him until his return in the 1990 adventure module “Vecna Lives!” (exclamation point included).

Meanwhile, the lich was developing more of its lore, including the “soul hidey place” more often known as a phylactery, though how it got this detail is a bit convoluted. The term is first mentioned in 1977’s AD&D Monster Manual: “The lich passes from a state of humanity to a non-human, nonliving existence through force of will. It retains this status by certain conjurations, enchantments, and a phylactery.” What is a phylactery? Well, the manual never tells us, but the greek term means a “protectant,” and was usually used for tefillin, small leather boxes used in Judaism. They contained verses from the Torah and could be strapped to the body, often on the arm or head, during prayer. How such an item would relate to lichdom is not explained, but it should be noted that 1979’s Dungeon Master’s Guide included three phylacteries as magic items. These were usable only by clerics, and were the Phylactery of Faithfulness, which helped a cleric retain their alignment; the cursed Phylactery of Monstrous Attention, which lured enemy monsters or even deities to attack; and the life prolonging Phylactery of Long Years. Even though it was published later, it seems probable that some notes on this sort of item existed and might have been the intention of the item mentioned in the lich’s write-up.

The idea that a lich’s soul resided outside its body was not put forward until a 1979 article in Dragon Magazine by another veteran game designer Len Lakofka, the original player of the character Leomund and his famous Tiny Hut. The article, “Blueprint for a Lich,” never mentions the term phylactery, but details how the lich uses an item enchanted with the Magic Jar spell to contain its soul and allow an escape should its body be destroyed. Eventually, the phylactery and the soul jar would become conflated, leading to the lich lore we know today.

Folklore

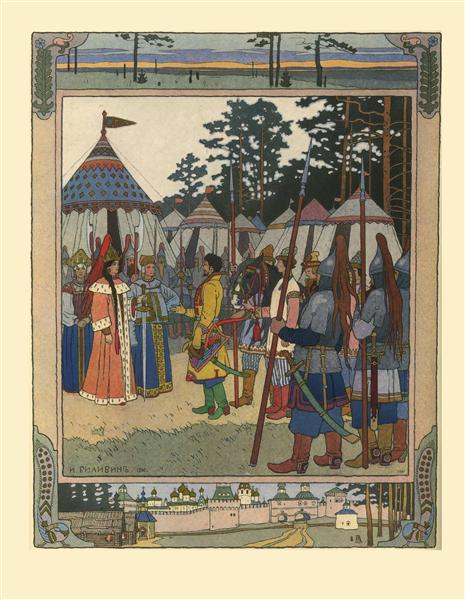

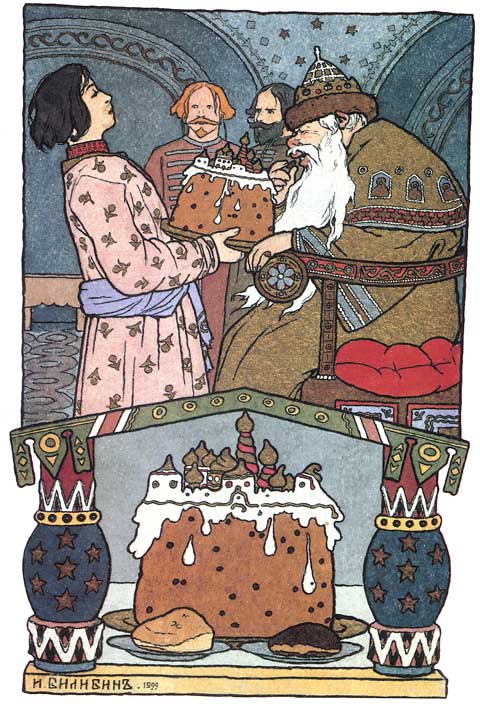

The story of a creature that keeps its soul, life, or heart outside of its body is an old one. In the Aarne-Thompson-Uther (ATU) index, it is type 302. It is an incredibly old tale, told all over the world; in fact, network analysis of the ATU story types found that this one is among the top 10 most central stories.1 Julien D’Huy, “Folk-Tale Networks: A Statistical Approach to Combinations of Tale Types,” Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics, Vol. 13, No. 1 (2019), https://www.folklore.ee/era/pub/files/jef-2019-0003.pdf In these tales, some villain (often an ogre) keeps its life force outside its body, and the hero must go on a quest to find and destroy it in order to defeat the monster. Possibly the most famous version of this tale is the Slavic version, in which the antagonist, Koschei the Deathless, has hidden his soul in a needle in an egg in a duck in a rabbit in a chest buried beneath a tree on the mythical island of Buyan. Koschei is a sort of ogre, but his name probably derives from the proto-slavic word *kȍstь for bone, and in fact the villain is sometimes called “Old Boney” in English versions. Though not exactly undead, this skeletal figure of immortality seems a likely candidate for part of the origin of the lich, despite his lack of spellcasting.

In the latest take on Vecna, the Vecna Dossier, the source of Vecna’s power is obscured as a mysterious voice that whispered to him. In older versions, this source was called the Serpent, though still shrouded in mystery. In my own personal head cannon, this can be none other than Baba Yaga; one possible etymology for “Yaga” is from the word for serpent, and it seems only fitting for me that the mother of all witches would have a hand in the creation of the first lich!