It’s Tuesday, 2/22/2022. Happy Twosday! For the occasion, I’d like to write about a doppelganger, of a sort…

Having been born in the waning days of the Cold War, I’ve been primed to always see Russia as a strange doppelganger to the USA. There were of course the lofty conflicts like east vs west, capitalism vs communism, and authoritarian vs democracy. But it was also at the level of pop culture, with everything from “backwards” letters like Я and И to the Russian reversal joke construction, “In the Soviet Union, TV watches you!” Marvel comics even had the Winter Guard, a team of bizzaro Avengers aligned with the Soviet bloc.

I have a similar experience reading Russian folktales. These stories follow familiar plots and feature similar motifs as the Western tales popularized by the Brothers Grimm and Disney. They are so close, in fact, that when there are disparate elements, they stick out all the more. If the same ideas appear in folklore from across the world, then Russian tales are in a sort of uncanny valley relative to Western Europe.

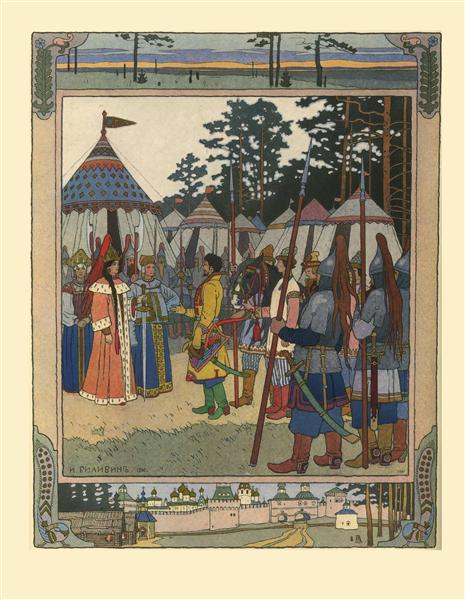

Take, for instance, the tale of Marya Morevna. Near the beginning, in a scene reminiscent of the story “Bluebeard”, Marya warns her new husband, Prince Ivan, not to look in a certain closet while she is away. In Bluebeard, it is the wife who looks into a room or closet against her husband’s warning to discover the titular Bluebeard’s macabre habit of murdering all of his previous wives; the rest of the tale involves the wife outsmarting and escaping her deadly paramore. In Marya Morevna, Ivan finds a man chained in the closet, but it turns out that this man is actually an immortal villain Koschey the Deathless. Ivan’s kindness allows the now freed bony man to kidnap Marya, and the rest of the tale is about Ivan’s rescue of her.

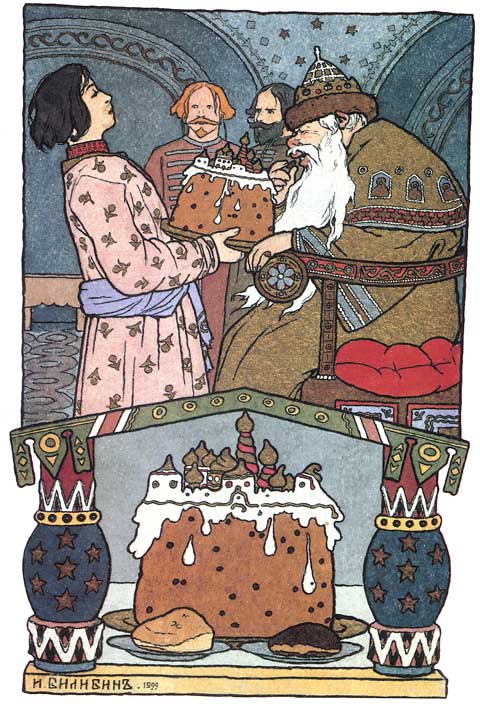

Another famous Russian tale is that of the Frog Tsarevna (or frog princess). Frog princesses do appear in Western tales, even in a Disney movie, but the more well known version involves a frog prince. In these stories, the frog is betrothed to a girl and only gets transformed back to its princely form through a conveyance such as a kiss, being invited into the girl’s bed, or, my personal favorite, being thrown against a wall. The frog tsarevna needs to work quite a bit harder for her transformation, proving her ability to sew, cook, and perform other traditional domestic duties better than her sisters-in-law. In some versions, her husband discovers and tries to hide her frog skin, which only causes further problems and the need for a rescue from, who else, Baba Yaga (link).

Finally, we could look at the Tale of Tsarevich Ivan, the Firebird, and the Grey Wolf. Wolves almost always take the role of villains in Western tales. The most famous examples would be the ‘big bad wolf’ from Little Red Ridinghood and the Three Little Pigs, but they also to turn up in about every other Disney movie from Beauty and the Beast to Frozen. The grey wolf of the Russian tale, on the other hand, is a supernatural helper; he helps Ivan to rescue a princess, to capture the firebird, and he even, at one point, brings Ivan back to life. This is another tale that has lesser known Western analogues, though in these the helper is almost always a cunning fox, a creature that has enjoyed a more positive (though not unambiguous) depiction.

I love how Russian tales offer an opportunity to view these familiar folktales in a new light. Given the recent wave of popularity of Eastern European motifs in shows like the Witcher and Shadow & Bone, I like picking apart what contributes to this setting. I’ve chosen these tales for comparison because they’re among the most popular in Russia and the West, respectively. But we can dig even deeper to find comparable tales.

The Aarne-Thompson-Uther index (or ATU) is an exhaustive list of folktale plots from around the world. Each plot type is numbered: so, for instance, the main plot of Marya Morevna is categorized as type 302, “Ogre’s Heart in the Egg.” Any tale from around the world in which a villain hides their heart or soul outside of their body (and there are many!) would receive the same classification. So what would we learn if we compared tales with the same classification? For instance, Cinderella vs Russia’s Vasilisa the Beautiful, both ATU 530? Sorry to end on a cliffhanger, but this is something I’d like to develop in future posts. Please subscribe below to stay tuned!