When writing about folklore and mythology, I’ll sometimes switch between talking about Eastern European, Slavic, and Russian tales. These are related, but not synonymous. I’d already been thinking about writing a post to clarify these terms; then, Russian dictator Vladimir Putin gave a ranting speech in which he justified his invasion of Ukraine with ahistorical claims about the history of Ukrainian nation and people, so I think the topic is more timely than ever. Please bear in mind that the following is a vast simplification of a millennium of history, but feel free to ask any questions in the comments below.

Where is Eastern Europe?

Eastern Europe as a category is a surprisingly modern phenomenon. It is usually used to describe the countries that had communist governments (either home grown or installed by the Soviet Union) after World War II. So, although they are in the east of Europe, Greece and Finland are usually not considered part of Eastern Europe because they were allied with the US (for Greece) or neutral (for Finland). Some areas of Eastern Europe, like modern Poland and Hungary, would have previously been lumped together with Germany and Austria as Central Europe. This term is gaining more popularity since the fall of the Soviet Union as a way for them to assert their historic connections to Western Europe.

Who are the Slavs?

The Slavs are an ethnic and linguistic group. All of the Slavic countries are in Eastern Europe, but not all countries in Eastern Europe are Slavic: Romania speaks a Romance language (ie, grouped with French and Spanish), Hungarian and Estonian are closer to Finnish, and Albanian is in its own language family. The Baltic languages (Lithuanian and Latvian) are somewhat closer to the Slavic languages but in their own category.

The Slavic languages are further subdivided into Western, Eastern, and Southern. So while there are many similarities between Polish (a West Slavic language) and Russian (an East Slavic language), there are even more similarities between Russian and Ukrainian (both East Slavic languages). Just like Danish and Norwegian, two Germanic languages, are much closer to each other than they are to German or English, also Germanic languages.

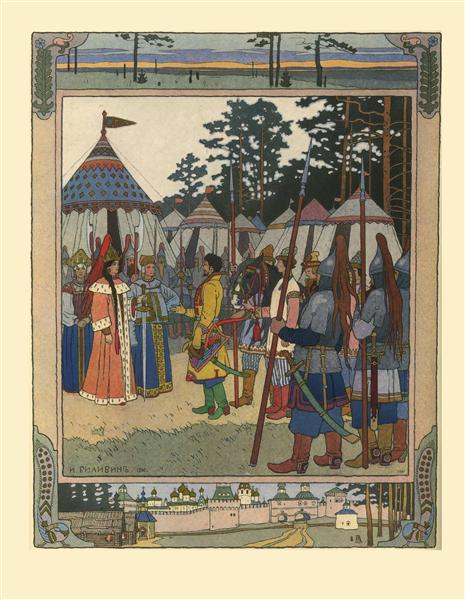

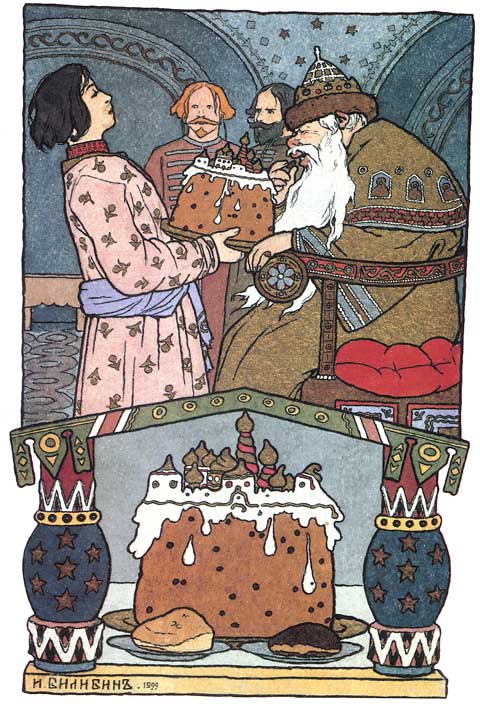

Unlike the Greeks or Norse, the Slavs did not write down their language before they were converted to Christianity, so much of what we know about their pagan beliefs is based on second hand information and guess work. Of what we know, there were similarities among all the Slavic groups, like the thunder god Perun. Their folk tales, too, are often very similar, with shared characters like Baba Yaga, Leshy, and Domovoi. There are also crossovers with non-Slavic groups: for instance, the vampire myth can be found in the Romanian strigoi, the Polish strzyga, the Albanian dhampir, and the East Slavic upyr, to name a few.

The Kievan Rus

So, we can find the history of many groups speaking Slavic languages in the eastern part of Europe as far back as the early Middle Ages, but for much of the history since, they were not organized into separate countries. One of the major exceptions was the Kievan Rus. With its capital in Kyiv (the capital of modern Ukraine), this country ruled an area spanning modern Ukraine, Belarus, and the west of modern Russia. It was founded by Vikings, but the majority of the people were Eastern Slavs. It traded with the Byzantine Empire and converted to the Orthodox Christianity of the Byzantines.

The Kievan Rus splintered and was conquered by the Mongols around 1240. Some 240 years later, when Mongol power was waning, the ruler of Moscow, Ivan the Great, was able to declare his independence from the Golden Horde. His grandson, Ivan the Terrible, would eventually declare himself Tsar of Russia. Thus, the Russian state tied itself to the historic Orthodox kingdom of the Kievan Rus.

Meanwhile, Kyiv came under the control of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Polish was the language of the nobility, but the Lithuanians, Belarusians, and Ukrainians maintained their unique identities. As the Russian Empire grew in power, conquering Siberia and reaching the Pacific, the Polish state entered a period of decline. In the 1700s, it was partitioned by its stronger neighbors: Russia, Prussia, and Austria.

The Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and the Russian Federation

In 1917, the Russian Tsar was overthrown, and most of what had been the Russian Empire became the Soviet Union. However, along the empire’s western border, non-Russian ethnic groups asserted their independence: Finland, the Baltics, Byelosussia, and Ukraine. In the wars that followed, Byelorussia and Ukraine were reabsorbed by the Soviet Union and a resurgent independent Poland, but Finland and the Baltics kept their independence. The Baltics were conquered again by the Soviets during World War II, along with the rest of modern Belarus and Ukraine.

As an empire that spanned across Eurasia, Russia had never been ethnically homogenous. The Soviets reorganized the old empire into a Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or SSRs. The SSRs were somewhat independent (the Ukrainian and Byelorussian SSRs had their own seats at the United Nations), but still subject to the central government in Moscow. The largest constituent republic was the Russian one, but even it contained multiple Autonomous SSRs for ethnic groups like Tatars, Chechens, Mordvins, and Udmurts. Still, Russians were the largest ethnic group, both in the RSFSR and the USSR as a whole. So, “Russian” and “Soviet” were considered synonymous in the West during the Cold War, but this disguises the fact that there were always non-Russians in both the old empire and the USSR. With the dissolution of the USSR, the SSRs became independent countries. The ASSRs remained within Russia, though Chechnya fought a bloody war trying to gain independence.

I hope this puts some of the current events in context. For my part, I love to study the culture and folklore of this region, and I desperately hope the people of Ukraine can soon live peacefully despite the whims of an autocrat.

Edit: earlier version of this post used “the Ukraine” instead of “Ukraine.” Sometimes I get caught in historicisms but I want to be more accurate to the moment. I’m still using “Byelorussia” to refer to the historic country and region, but “Belarusian” to refer to the ethnic group.